Why do I need to know about knife crime (in 60 seconds)

Knife crime is a serious and growing issue affecting children and young people across the UK. Over the past decade, knife-related assaults and homicides involving teenagers have risen significantly - even as overall youth violence has declined. While only a small percentage of young people are involved, the consequences are devastating: serious injuries, deaths, and communities living in fear.

Many children and young people carry knives out of fear or for status, with underlying factors including poverty, exploitation, and/or trauma. Knowing about knife crime helps understand the risks, spot warning signs, support those affected, and be part of the solution - whether you're a parent, teacher, peer, or community member.

Introduction

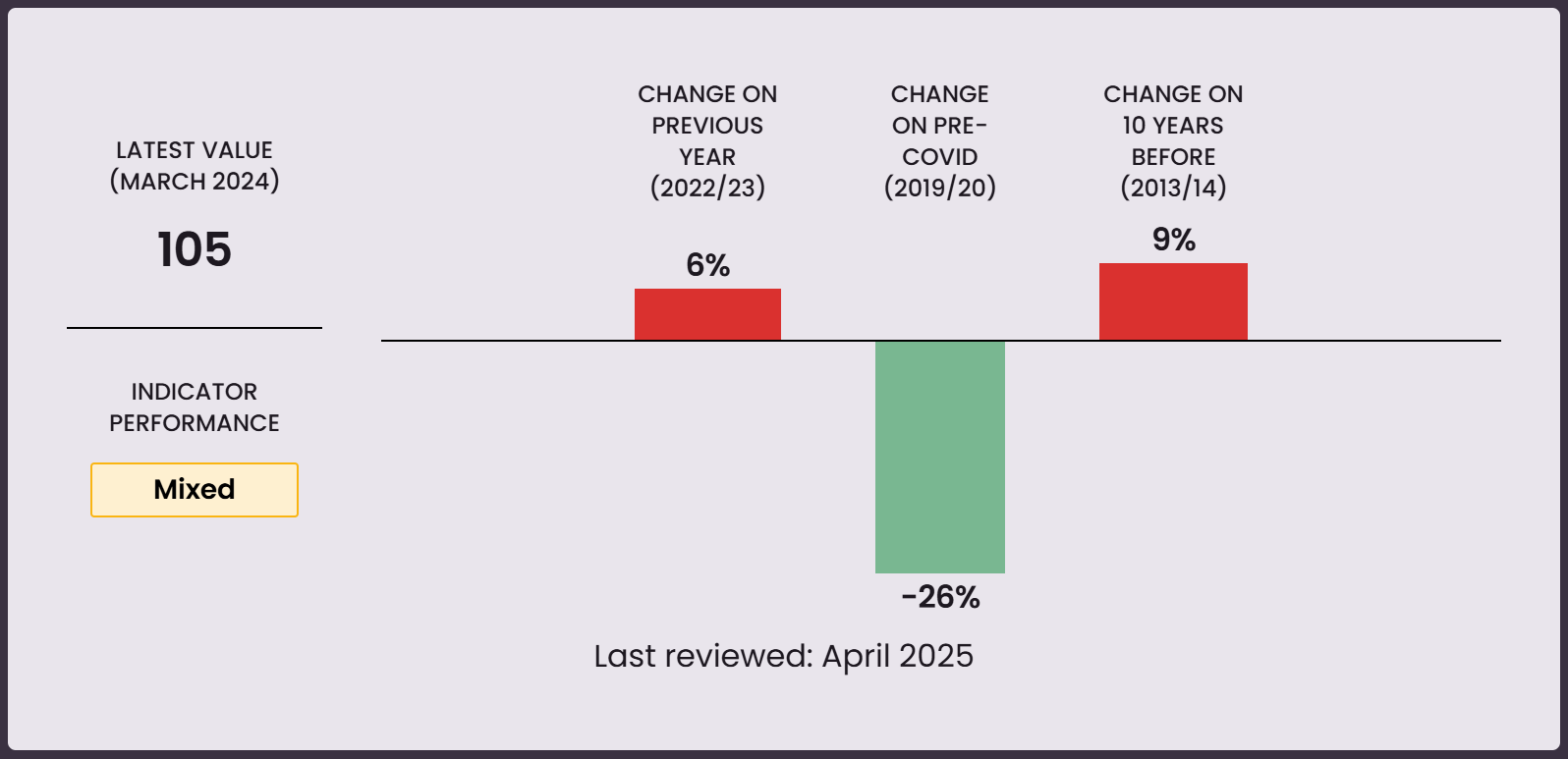

Knife crime amongst children and young people has again been bought into the spotlight through the release of Adolescence on Netflix. Knife crime is rarely out of the news, and whilst there was a dip in the number of offences during the Covid-19 lockdowns, the annual number of offences involving a blade or sharp instrument (the police definition of knife crime) has roughly doubled in the last decade (House of Commons Library). Offences include stabbings, robberies, and assaults with knives.

This is in stark contrast to the wider picture in relation to violent crime, with the Office for National Statistics stating in its analysis of data to the year ending March 2024:

While there is no single measure of violent crime, the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) has shown gradual decreases in violence with and without injury, and domestic abuse, over the last ten years. It has also indicated a rise in sexual assault. Over the same time period, trends in CSEW stalking and police recorded homicide have remained relatively flat.

Young people and knife crime

Involvement of young people in knife crime has also grown: the Youth Justice Board reports that just over 3,200 knife or offensive weapon offences by children resulted in a caution or sentence in 2023/24 – whilst this has been declining for six consecutive years, it is still about 20% higher than a decade ago. We do need to have this in context however, the latest census data (Office for National Statistics) suggesting that there were just over 5.5 million children and young people aged 10-17 living in England and Wales in 2021. This suggests that whilst knife crime should not be ignored and will have a significant impact on children and young people who are affected by it, as with a lot of issues related to safeguarding, we need to be able to identify the cohorts involved.

When it comes to young people as victims of knife crime, the data is more concerning. Both homicides and injuries among young people as a result of knife crime rose in the mid-2010s and has continued to rise. For instance, in 2022/23 467 children (under 18) were treated in hospital for assault by a sharp object – a 47% increase from 318 a decade earlier (Youth Endowment Fund). Positively, such incidents involving children and young people appear to have peaked around 2018/19 and have since declined slightly (with a drop during 2020), but they still remain well above early-2010s levels.

Similarly, the number of young homicide victims has increased: in 2022/23, 99 young people aged 16–24 were homicide victims, compared to 87 in 2012/13. A very large share of murders of children and young people involve knives – about 82% of homicides of 13–19-year-olds in 2022/23 were committed with a knife. These trends illustrate that knife violence affecting children and teens worsened over the decade, even though overall youth violence (including offenses without knives) followed the wider trend found in the Crime Survey for England and Wales, showing positive declines.

Notably, the number of proven violent offenses by 10–17-year-olds has nearly halved in ten years (14,298 in 2022/23 vs roughly double that in 2012/13), suggesting fewer children and young people are being convicted of violence. However, this downward trend in youth offending has levelled off recently, and youth knife crime remains a serious concern nationally (Youth Endowment Fund).

It’s worth noting regional differences and the broader national overview. Knife crimes are statistically more prevalent in metropolitan areas across England and Wales, with the Home Office stating that 30% of all offenses relating to knife-enabled crimes (to the year ending September 2024) were recorded by the Metropolitan Police Service and 9% by West Midlands Police.

Whilst London and other urban areas have long been hotspots, research suggests that in recent years the problem has begun to spread more widely across England and Wales.

In contrast, Scotland – which faced a severe knife violence problem in the 2000s – has seen a dramatic long-term drop in youth knife crime after adopting a public-health approach. The rate of handling offensive weapons in Scotland fell by 44% from 2007 to 2020 (from over 10,000 cases to around 4,484) (No Knives Better Lives). Scotland’s homicide rate among teens also declined to the point that, in 2017, none of the 35 youth knife fatalities in Britain occurred in Scotland (Of 35 children and teenagers killed with knives in Britain in 2017, not ...). (Recently, Scotland has noted a slight uptick, underscoring the need for continued vigilance.) This contrast highlights that while England and Wales have seen rising youth knife crime over the decade, targeted strategies can lead to improvements, as seen in Scotland.

Fear of knife crime

Beyond fatalities, the fear and knock-on effects of knife crime among children and young people are significant. Surveys indicate many young people worry about knife attacks – roughly half of children and young people say they are concerned about knife crime in their local area (Vision of Humanity). One recent analysis estimated about 3% of children aged 10–15 feel it is likely they will be attacked with a weapon in the coming year (The Independent), which, while a small percentage, represents thousands of children living in fear.

The prevalence of knife-carrying among some young people (often for self-protection or due to peer influences) contributes to a cycle of violence and anxiety (Ofsted). Communities in parts of London, the West Midlands, and other affected regions report that knife crime has become a persistent concern influencing children and young people’s behaviours and safety decisions (e.g. avoiding certain areas or travelling in groups). Arguably therefore, the current situation is that knife crime involving under-18s remains a serious issue in England and Wales, with recent data showing high (if not worsening) levels of youth victimisation. Data also shows a degree of overlap between victims and perpetrators of violence:

48% of teenage children who said they’d committed violence were also victims of violence. This proportion increased to 81% for those who said they were part of a gang, 78% for those supported by a youth offending team and 64% for those receiving free school meals.

2018 research by the Mayor of London Office for Policing and Crime backs this up, with a quarter of young people surveyed reporting that they know someone who has carried a knife, or who is in a gang. The same survey noted that certain groups showed greater “vicarious exposure to these issues” (p.17), noting that children who attend pupil referral units are one cohort where exposure to knives is greater, increasing to around 50%.

Strategies for Reducing Knife Crime

Overall, there has been a multi-faceted strategy to curb knife crime, focusing on tougher laws, policing tactics, and preventative initiatives. Key elements include:

- Tougher Laws and Sentencing: The government has tightened legislation on weapons and punishments over the last decade. It is illegal to carry a knife in public without good reason (maximum 4 years imprisonment) (House of Commons Library), and since 2015 repeat offenders face a mandatory minimum custodial sentence (6 months for adults, shorter but still custodial for 16–17-year-olds). The Offensive Weapons Act 2019 banned certain dangerous items (e.g. “zombie knives” and knuckle-dusters) and made it harder for under-18s to buy knives online (requiring identity checks and banning home delivery). In 2024, the law was further strengthened to ban more blade types (e.g. specific machetes and so-called “ninja swords”) and to require retailers to report suspicious knife sales to police (The Education Hub).

Courts have also been encouraged to use Knife Crime Prevention Orders (civil orders to restrict and monitor those likely to offend) and have imposed stiffer sentences for knife-enabled crimes, especially when involving children and young people as victims. These legal measures aim to deter carrying and facilitate the removal of weapons from circulation. - Police response: Police forces have scaled up targeted efforts to detect and discourage knife carrying. A prominent example is Operation Sceptre, a national coordinated week of action across police forces. In a single week of Operation Sceptre in May 2023, police across England and Wales seized around 9,700 knives from the streets and made 1,693 arrests (829 for knife-related offences) (National Police Chiefs' Council).

Tactics during such operations include weapon sweeps of parks and public areas, deployment of knife detection arches and wands in public places, knife amnesty bins for anonymous weapon drop-off, and increased stop-and-search patrols in hotspots. Outside of these operations, many police forces have dedicated Violent Crime Task Forces or knife crime units focusing on youth gangs and habitual knife carriers.

Stop-and-search use has risen in hotspot areas under powers like Section 60 (no-suspicion weapons searches) as a short-term suppression tactic, though this has raised concerns about disproportionately targeting specific racial groups (House of Commons Library). Additionally, new tools like Serious Violence Reduction Orders are being piloted, which allow police to search known knife offenders routinely.

In some force areas, police also work closely with schools – assigning school liaison officers and giving educational talks – as well as using intelligence-led approaches (for example, monitoring social media for threats or illegal knife sales). The aim is to pair crackdowns on knife carrying with outreach to dissuade children and young people from arming themselves. - Early Intervention and Community Programs: Recognising that enforcement alone cannot solve the problem, the UK government and local authorities have invested in preventative initiatives, often adopting a public health-style approach.

Following a spike in youth violence, the Home Office launched the Serious Violence Strategy in 2018 emphasising early intervention in the lives of at-risk children and young people (Ofsted). This was followed by funding the creation of Violence Reduction Units (VRUs) in areas across England and Wales. VRUs bring together police, social services, education, and healthcare to identify children and young people at risk of being drawn into violence and provide holistic support (such as mentoring, mental health support, and employment opportunities).

Made law in 2022, the Serious Violence Duty requires local authorities, police, health agencies and others to collaborate on tackling serious violence, ensuring a multi-agency plan is in place. There has also been significant investment in youth services: for example, the Youth Endowment Fund was established in 2019 to trial and evaluate violence prevention programs (House of Commons Library).

Community organisations and charities play a crucial role as well – projects like the St. Giles Trust’s SOS Programme and the Ben Kinsella Trust workshops educate young people about the dangers of knife carrying, often using ex-offenders or the stories of knife crime victims to deliver powerful messages. Initiatives have also included programs such as hospital “teachable moment” programs where youth workers have been located in emergency rooms to engage young stab wound victims (to prevent retaliation and recurrence).

More recently (2024), the government launched a Coalition to Tackle Knife Crime that brings together police, schools, health services, youth workers, victim families, tech companies, and sports groups to understand and address the root causes of youth violence. Plans were also announced to establish “Young Futures” prevention partnerships to coordinate local support for at-risk teenagers. These efforts indicate a strategy increasingly focused on addressing underlying factors – such as poverty, exclusion, and gang grooming – that drive young people towards knife crime (Ofsted). By improving youth opportunities, providing positive role models, and intervening early when children show signs of risky behaviour, authorities aim to reduce the incentive or need to carry knives. - Public Awareness and Education Campaigns: The government and police have run public campaigns to change attitudes toward knife carrying. For example, the Home Office’s #KnifeFree campaign (launched in 2018) used social media, advertising and school materials to share real-life stories of young people who chose to live “knife-free” and to highlight the legal consequences of carrying a knife. Police forces regularly visit schools to deliver talks on knife crime, often alongside charities or even reformed ex-offenders, to dispel myths (such as the idea that carrying a knife offers protection) and to encourage pupils to report concerns.

Surveys have found that fear is a major reason youth carry knives (Ofsted), so these educational efforts stress that carrying a weapon actually increases one’s risk (for example, a young person is far more likely to be stabbed with their own knife if they carry one) and that there are safer ways to seek protection.

Alongside traditional media, social media companies are being pressured to remove content that glorifies knife violence and to shut down online markets for knives sold illegally to minors (The Education Hub). By changing the cultural perception of knives among young people and the wider community, these campaigns hope to make knife-carrying socially unacceptable and reduce youth demand for weapons.

Why do children carry knives?

Research by Ofsted based around educational settings in London identified there were three categories that children would likely fall into in relation to risk of knife carrying:

- The highest level of risk is for those children who have been groomed into gangs for the purposes of criminal exploitation.

- Underneath this lies a group of children who have witnessed other children carrying knives, have been the victim of knife crime or know someone who has carried a knife for protection or status-acquisition or who are encouraged to believe knife-carrying is normal through the glamorisation of gangs and knives on social media.

- Then there are children who carry knives to school as an isolated incident. For example, they may carry a penknife that a grandparent has gifted them.

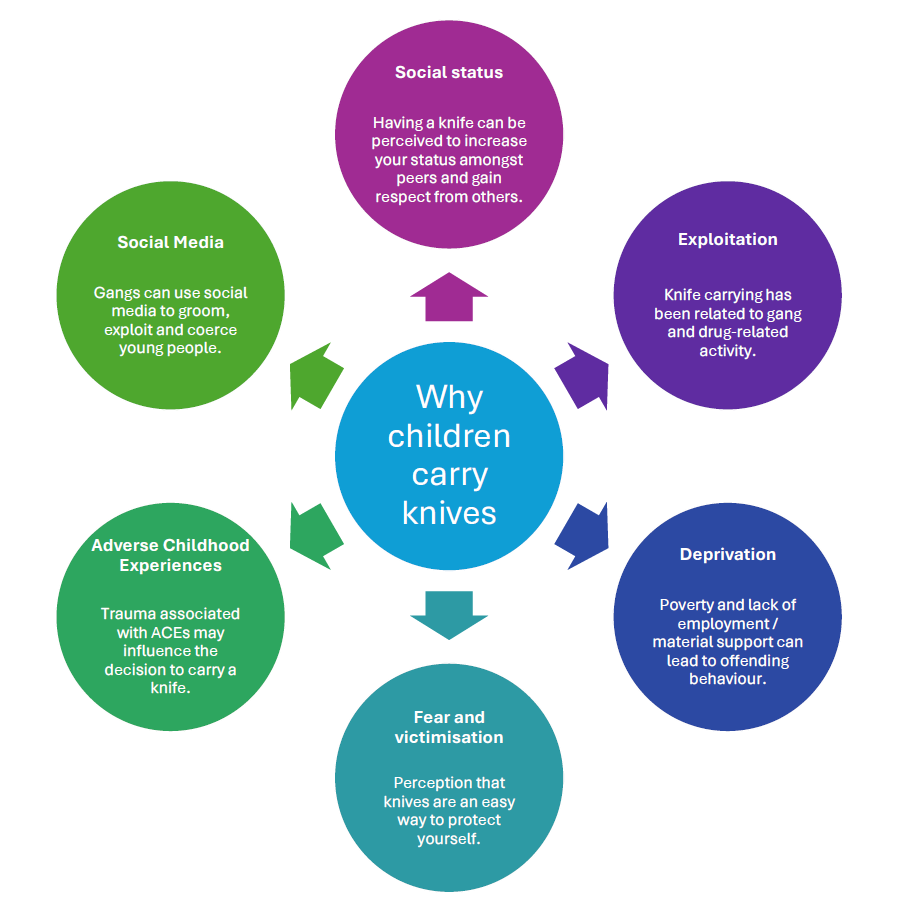

The Youth Justice Board build on the first and second bullet points above suggesting that it is the interplay of six factors that drive knife crime:

However, the Youth Justice Board do caution that “it is difficult to establish the prevalence of the reasons behind knife carrying”.

This links with Ofsted’s research which identified that children who have:

experienced poverty, abuse or neglect or are living within troubled families. They may also experience social exclusion due to factors such as their race or socio-economic background […] those likely to be involved were also more likely to be low attainers academically compared with their peers. (p.5)

However, in a challenge to the ordering of risk presented by Ofsted, the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (2018) report that their literature review found a large number of studies that evidenced a correlation between income inequality and violence, with there being a greater correlation with violent offences such as homicide and assault. The same literature review identified that mental ill health and adverse childhood experiences are linked with aggressive behaviours, whilst specific triggers for knife carrying could be linked to being victims of bullying and the dynamics of victimisation and humiliation – this suggesting that a significant driver for carrying knives is protection and status acquisition.

On the subject of child criminal exploitation, the literature review suggests that county lines and the use of violence as a means of achieving business objectives may be key in the rise of knife related violence in rural areas.

Browne, Jareno-Rippoll and Paddock (2024) support the view that it is not a “one-size fits all” approach:

Our research shows that knife offenders exhibit a considerable degree of diversity, indicating that there may be subtypes within this population. For instance, female perpetrators tend to commit offences in domestic settings, whereas males are more likely to do so in community settings (Gerrard et al., 2017).

Furthermore, knife offenders who are affiliated with gangs differ from those who are not. Gang-related knife crime involves 'instrumental aggression' as a means to an end to protect 'territory' for illegal drug sales. By contrast, non-gang-related knife crime involves young people with previous adverse experiences (ACEs) acting alone and showing 'hostile/expressive aggression.' (Jareno-Ripoll et al., 2024).

A BBC News article (March 2025) shows how difficult the interplay between home and gang life can be, and the different factors that lead one young person, Michael, to stab someone, coupled with the realisation once arrested any respect that may have been built up, any apparent support from the gang means nothing.

So, what does this mean for education settings?

In their research, Ofsted found that for the majority of settings their primary stance was zero tolerance toward weapons along with clear expectations and robust policies: for example, most settings were found to have strict behaviour policies that mandated immediate exclusion for any student found carrying a knife on premises.

There are two aspects to maintaining a safe environment:

- Maintaining a physically secure environment

The challenge is how your setting would proactively maintain a secure environment. Does this mean for instance, supervising entrances and exits at the start and end of the day, monitoring areas like gates and bus stops, and liaising with local police to ensure a visible presence during high-traffic times? Fortunately, serious knife incidents on school grounds are relatively rare and tend to be isolated events. Does this serve to provide a perception of safety and reassurance? Inspectors have found that where these features are present, school leaders were generally confident that pupils were safe on site.

Some settings have gone further, implementing additional security technology. Schools are empowered by law to screen students for weapons; metal detector arches and handheld wands can be used at entry points if a headteacher deems it necessary. Settings in higher-risk areas may also choose to also conduct random searches in conjunction with technology, though these approaches are not widespread. The government guidance leaves it up to each setting to decide.

Of note is that studies indicate the most dangerous time for children and young people is often right after school (around 4–6pm), when they are off the premises and potentially vulnerable to street crime. Some settings acknowledge this risk and extend their duty of care beyond the gate – for example, teachers may patrol nearby bus stops or routes home, and schools coordinate with police to protect pupils on their journeys (Ofsted). Thought also needs to be given as to what the setting’s response would be to any violent incident involving students off-campus and whether this would lead to disciplinary action in the setting. Therefore a knowledge of the surrounding area and the wider contextual lived experience of your students is key.

For all settings, emergency preparedness need to be a part of safety planning – the Department for Education has issued detailed school security guidance which includes handling lockdowns or violent intruders. Staff should be trained in safeguarding responsibilities and drills conducted so that everyone knows how to respond if a serious incident occurs on site. - Developing a safe culture

Arguably, most of the focus should be on preventive policies and developing a safe culture: some of this may include physical actions such as enforcing uniform and bag checks to develop a sense of pride and belonging, others may include more generalist approaches such as encouraging a culture of reporting (so that if a child or young person suspects a peer might have a weapon, they feel safe telling staff). It may also include working closely with external agencies (such as Safer Schools Officers (police) where assigned).

Education settings can also be key venues for preventative programs and outreach to steer young people away from knife crime. Is knife crime awareness incorporated into your curriculum and pastoral care. Does your Personal, Social, Health and Economic (PSHE) curriculum include dedicated lessons talking about the dangers of carrying weapons and managing conflict? Is there the option to host external speakers? For example, education settings may invite local police or charities to run anti-knife workshops. Specialist programs like the Ben Kinsella Trust’s exhibitions use immersive experiences to show students the real consequences of knife violence. In London, the Mayor’s Office has supported programs sending knife crime educators (often including victims’ parents or ex-offenders) into schools to share testimonies.

Another approach is peer-led education: some youth organisations train young people to campaign against knife carrying among their classmates. Mentoring and counselling are provided for pupils deemed at risk, and in some areas, schools work with youth workers or psychologists to support children who have been victims of violence or those showing behaviour that might lead to offending.

Addressing vulnerabilities

Regardless of where the perceived vulnerabilities stem from, it is important that as part of our safeguarding duties we work to address the identified vulnerabilities and empower children and young people to stay safe from knife crime.

For schools this can arguably be seen as yet another area to add to an already overloaded safeguarding agenda, however if the underlying issues are potentially linked to poverty, bullying, mental health, emotional harm and child criminal exploitation then there is less of a need to reinvent the wheel, and this can be done regardless of whether the provision is mainstream school, pupil referral unit, or residential children’s home.

That is not to say that this is solely an issue for individual organisations to have to address. The Guardian (2019) quoted the leader of charity Redthread as warning that victims of serious or fatal knife attacks have usually attended A&E units up to 4-5 times previously with less serious injuries. The young people referred to here will have potentially been involved with a number of agencies and so there may be patterns that can be identified by multi-agency cooperation and the use of chronologies.

Ofsted recommend that local responses should involve education settings designing strategies to address knife crime and serious youth violence. They argue that whilst there is Department for Education guidance around the powers for settings to search and screen pupils as well confiscating items they may find, there is a lot of variation around implementation. There is also apparent variation between organisations as to when the police are involved – the Criminal Justice Act 1988 (s.139A) sets out that with the exception of a folding pocketknife which has a blade of 3 inches or less, having any article with a blade or that is sharply pointed in an education setting is an offence.

As we have seen, education settings generally do prohibit the carrying of knives and take a robust approach. This should include close links with the Police, reporting of knives and intelligence about tensions within the school which are likely to lead to knife violence. However, this should run alongside the underlying question of “what is daily life like for this child?” If we can begin to answer that question, then we will be able to start to understand why they are carrying the knife in the first place – e.g. around self-preservation, vulnerability or intent to harm. The Ofsted research provides an example of this, suggesting there were examples of teenage girls carrying knives in order to self-harm. In this case how do you safeguard effectively whilst managing the risk? Different people will always have differing views on this depending on personal and professional viewpoints, but regardless of how the issue of having a knife is managed there also needs to be consideration of the safeguarding needs of the child.

Exclusion

Whilst exclusion may solve an immediate problem and safeguard the students in the setting, how can children be safeguarded when excluded? Without the structure and protection of an education setting children can be at greater risk of being groomed by exploiters. Many local authority threshold tools will identify either multiple fixed term exclusions or a child being permanently excluded as a marker for potential social care involvement on a child in need basis. Therefore, at the point of exclusion consideration should be given to what is known about the child being excluded and whether a referral to social care is required. Such consideration should include what is known about the child, their home circumstances and peer networks – for example, are there any of the vulnerabilities present that would increase their risk of exploitation?

Some children and young people may be groomed to do certain things to get themselves excluded so that there is potentially less involvement from agencies and fewer protective factors. Groomers are constantly evolving to avoid a child’s behaviour flagging safeguarding concerns and this is therefore potentially another means to achieve this aim.

The underpinning vulnerabilities and needs of children, whether involved in child criminal exploitation or other forms of knife crime, should form part of your school’s safeguarding strategy. Safeguarding Network can help with our underpinning safeguarding curriculum for staff in-house training. Every month we provide DSLs with bite-size training materials to deliver to staff, increasing awareness, developing skills and providing a framework to respond to the needs of your pupils. Our aim is to ensure staff see things earlier, react effectively and that organisations are skilled at utilising their local networks to get children, young people and their families the support they need to reduce vulnerability to issues such as knife crime, either as a perpetrator or a victim. Contact us to be shown around our materials, or join now.

Conclusion

It is accepted that after a period of knife crime reducing, it is currently on the rise again. We do however need to maintain an awareness of the wider picture along with the underlying drivers for the increase to ensure that responses are appropriate. As always however, in every child that feels the need to carry a knife there are vulnerabilities that need to be identified and addressed to ensure that that child (potentially both a victim and perpetrator) is safeguarded.

Other resources include:

- https://noknivesbetterlives.com/ - an initiative supported by the Scottish Government to promote knife crime prevention work. Resources include toolkits and lesson plans

- https://www.knifefree.co.uk/ - a UK Home Office campaign providing real stories and seeking to quash misconceptions about carrying knives

- https://benkinsella.org.uk/resources-for-teachers-and-practitioners/ - preplanned KS2, KS3 and KS4 lessons based on video testimony from ex-gang members, victims and offenders.

What do I need to do?

- Check your staff are aware of requirements around issues such as child criminal exploitation and contextual safeguarding- our resource page can help.

- Provide your staff with update training in a team meeting. Members of Safeguarding Network can access our update packages, presenter notes, handout and quiz to test staff knowledge. Log in or find out more.