Introduction

The overview report of the Serious Case Review into Child Q makes for difficult reading. Suspected of carrying drugs, Child Q was strip searched (involving the exposure of intimate body parts) by police officers who attended the school without an appropriate adult being involved or there being challenge on the part of school staff. Very early on in the overview report the author is clear that “the strip search of Q should never have happened and there was no reasonable justification for it.” (para. 2.3, p.6). There has been a significant fallout as a result of the incident and in this safeguarding insight I do not intend to revisit these arguments, but instead look at the less well known role of appropriate adult, and how this role encapsulates a safeguarding approach within the criminal justice system.

The Appropriate Adult

How the Police conduct themselves when a person is detained and / or questioned is covered by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) Code C. In paragraph 1.7 the PACE guidance advises that “The role of the appropriate adult is to safeguard the rights, entitlements and welfare of juveniles and vulnerable persons”, with there being further elaboration that the appropriate adult (AA) is expected (my emphasis) to observe that the police are acting properly and fairly in relation to a vulnerable detained persons rights and entitlements, as well as helping the detained person understand their rights.

Equally important is that if the AA considers that the rights of the detained person are not being respected, or the police are not acting properly in their dealings with a detained person, the AA is expected (my emphasis again) to speak to an officer of the “rank of inspector or above”. This therefore means that if the AA is not happy about something there is clear recourse to a senior officer who can then review and determine what steps should be taken. The active nature of the AA role is reinforced in Home Office Guidance for Appropriate Adults, which states that the AA is not just an observer.

Safeguarding is therefore inherent within the AA role – this could be as basic as an AA reviewing the custody record of a detained person to check that the detained person has been given regular opportunities to access food and fluid. It is expected that the AA will support the detained person to understand what is being said to them allowing the detained person to participate fully in the process. For anyone requiring an AA, this can be a crucial part of the role with many people – in my experience some people will default to answering “yes” or “no” as they look for what they see is the quickest and easiest route out of the predicament they find themselves in.

An example of this was given on speech and language training I attended a number of years ago. The trainer talked about a young person who was in front of magistrates and was asked by the lead magistrate whether they had any remorse for the actions they had committed. The young person answered “no” and this led to him getting a significant sentence for the offence. When the speech and language therapist spoke to the young person after court, they asked about the young person’s answer, as they knew that he was remorseful. The young person stated that he did not know what remorse meant and was afraid to ask. He had however learnt through his childhood that if he answered “no” to most questions he was less likely to get into trouble. In this case however it had not worked out that way. Therefore, as an AA, our role is to step in and check that the young person knows what they are being asked and thereby ensuring that the answer they give is the correct one, as opposed to one given through lack of understanding.

A colleague of mine once gave me a clear example of the impact of this in interview. The young person in question had been arrested on charges of rape. In interview, the officer started the questioning by seeking to clarify that the young person knew that they were being interviewed due to an allegation of rape. This was delivered more as a statement and not a question, leading to the young person agreeing with the officer. The AA stopped the interview at this point and asked the young person to define rape as a way of checking their understanding. As a result of this it became very clear that the young person’s understanding of rape was very different to the legal definition of rape. Had this gone unchallenged the young person may have admitted to things within the interview without a full understanding of what the consequences could be.

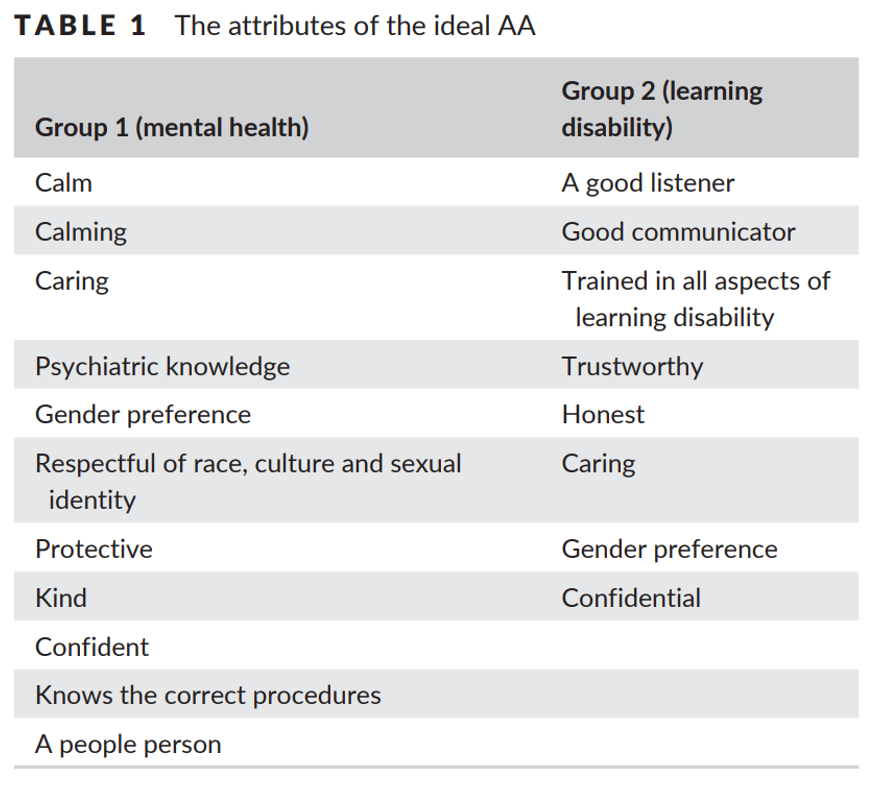

The role of AA is therefore a vital and powerful role for children and vulnerable people when detained by the police. The AA does not and is not required to give legal advice – this is the purview of solicitors. Research with vulnerable adults published in 2017 identified the attributes that made an “ideal” AA. The research had two focus groups, one group being individuals who suffer from mental ill health and the other group having recognised learning disabilities. The groups suggested the following:

As this research shows, the main attributes are linked with being a caring and trustworthy individual who will stand up for the rights of individuals.

The role of AA is not restricted to specific individuals, in relation to children and young people under the age of 18, PACE guidance sets out that the AA can be:

- the parent, guardian or, if the juvenile is in the care of a local authority or voluntary organisation, a person representing that authority or organisation (see Note 1B);

- a social worker of a local authority (see Note 1C);

- failing these, some other responsible adult aged 18 or over who is not:

- a police officer;

- employed by the police;

- under the direction or control of the chief officer of a police force; or

- a person who provides services under contractual arrangements (but without being employed by the chief officer of a police force), to assist that force in relation to the discharge of its chief officer’s functions,

- whether or not they are on duty at the time.(para 1.7)

The only exceptions to someone acting as an AA are if they are suspected of being involved in the offence, if they are a victim of or witness to the offence, involved in the investigation in some way or, crucially, if they have “received admissions prior to attending to act as the appropriate adult”. It is therefore entirely plausible that staff within your setting may be an appropriate adult for children and young people in your care.

Whilst the AA role is most often associated with detained individuals who are being held in custody at a local police station, the same Home Office guidance mentioned above states that an AA is entitled to be present “subject to strictly limited exceptions during any search of the detained person involving the removal of more than outer clothing”. As we saw in the case of child Q, this can therefore mean that the role of AA extends outside of custody centres.

Necessity and proportionality

Annex A of the PACE guidance covers intimate and strip searches, and in the first paragraph sets out that the “intrusive nature of such searches means the actual and potential risks associated with intimate searches must never be underestimated.”

Child Q’s words in the overview report emphasise the impact the search had on her:

Someone walked into the school, where I was supposed to feel safe, took me away from the people who were supposed to protect me and stripped me naked, while on my period.

Child Q’s mother reinforces this, telling the review:

Child Q is a changed person. She is not eating, every time I find her, she is in the bath, full of water and sleeping in the bath. Not communicating with us as (she) used to, doesn’t want to leave her room, panic attacks at school, doesn't want to be on the road, screams when sees/hears the police, and we need to reassure her.

A 2022 insight by the House of Commons Library in response to the furore around Child Q identifies that police have a clear set of rules which are intended to protect dignity, minimise embarrassment and prevent misuse of the power. These include:

- Reasonable and necessary: There must be reasonable grounds to justify the search. Searches exposing intimate body parts should not be treated as routine and should not be done simply because nothing was found in a standard search.

- Oversight and governance: Officers must consult with a supervisor before conducting the search.

- Privacy: The search must not be conducted in view of the public and must be conducted by an officer of the same sex as the person being searched.

Necessity and with it proportionality are concepts that are used throughout legislation to set boundaries around the level of intervention used. For example, government guidance around the disciplining of pupils states that a punishment must be proportionate (p.7). Children’s home’s regulations set out that any restraint of children or young people involving the use of force should only have the amount of force applied that is necessary and proportionate (p.48). Souliotis (2015) identifies that the principle of proportionality is a legal construct to allow for reconciliation between competing rights and demands. If we take a school punishing a pupil as an example, it would be disproportionate for the school to exclude a pupil for swearing in the classroom as there is a need to balance up the impact on the pupil of the exclusion against the harm caused by their swearing.

As identified by the British Institute of Human Rights (BIHR), proportionality is enshrined in the UK’s human rights law, guiding all public and professional bodies to ensure that the “least restrictive option available must be picked to meet the legitimate aim” (2022) – this is then further clarified by setting out that the option picked must not only be the least restrictive but also be non-discriminatory. The impact of this is that every situation should be assessed on its own merits as what may be less restrictive for one person may be more restrictive for another. Within this therefore there is the initially consideration of necessity – is there a need for the response that is being proposed?

Scotland Yard is reported to have said that the officer’s actions “should never have happened” and were “regrettable” and issued an apology. The statement issued by the Metropolitan Police suggests that Child Q was searched under s23 of the Misuse of Drugs Act following a preliminary search by school staff. This section authorises the police to search individuals if they have "reasonable grounds to suspect that any person is in possession of a controlled drug in contravention of this Act" (s23(2)). Reasonable is a word that we also see persisting in relation to safeguarding but with very little information to back up what it means. A parent or carer can potentially defend their smacking of a child by arguing that it was reasonable punishment, however as identified by the Surrey Safeguarding Children Partnership, what amounts to reasonable punishment is not defined and dependent on the circumstances of each case. Similarly, government guidance for schools issued in 2013 relating to the use of physical restraint is titled “Use of reasonable force in schools”, but the only definition of reasonable appears to be that it means using no more force than is needed (p.4).

It can therefore be argued that the definition of reasonable links with the positions set out above around looking at whether the proposed action is necessary and proportionate, thereby establishing a clear framework by which to determine whether what is being proposed is the right thing to do.

Strip searches and intimate searches

The College of Policing sets out the conduct that officers are expected to follow when searching someone, and advises that “Special consideration should be given to menstruating detainees. […] Where a detainee has menstrual products removed as part of a strip or intimate search, they should be offered a replacement without delay” – this being of significance as this was reportedly not done in the case of Child Q. There however differences in requirements between a strip search (where an individual is required to remove more than their outer clothing with the definition of outer clothing including shoes and socks and the process may include exposure of intimate areas) and intimate searches (broadly speaking searches involving the examination of bodily orifices other than the mouth).

Intimate and strip searches are covered by Annex A of PACE Code C with the College of Policing providing specific guidance in relation to such searches of children and young people. Intimate searches must be authorised by someone with the rank of inspector or above where there are reasonable grounds (emphasis added), adding that if the intimate search is for drugs offences then written consent of the individual to be searched must be obtained. Where this is a child or young person (i.e. under the age of 18) who is aged between 14 and 18, the consent must be obtained from the young person and their parent or guardian. Where the child is under 14 the parental consent alone is sufficient. Guidance is however clear that “Irrespective of the child’s age, the seeking and giving of consent must take place in the presence of an appropriate adult.” (College of Policing). Note that no such consent is required for a strip search.

Regardless of the type of search taking place it must be in the presence of an appropriate adult. Guidance is also clear in stating that:

(d) the search shall be conducted with proper regard to the dignity, sensitivity and vulnerability of the detainee in these circumstances, including in particular, their health, hygiene and welfare needs to which paragraphs 9.3A and 9.3B apply. Every reasonable effort shall be made to secure the detainee’s co-operation, maintain their dignity and minimise embarrassment. Detainees who are searched shall not normally be required to remove all their clothes at the same time, e.g. a person should be allowed to remove clothing above the waist and redress before removing further clothing;

Conclusion - the Appropriate Adult and safeguarding

As we can see, the guidance for police around the use of searches is, with some nuances in relation to consent as identified by the overview report in relation to Child Q, clear in relation to ensuring when and how searches should be conducted with there being a clear role for an appropriate adult throughout.

Through the course of this insight we have identified how the appropriate adult would inherently ensure a number of checks are completed which act to safeguard a child or young person if they were in a similar situation to Child Q.

- Is the search necessary and proportionate? The argument in the Child Q overview report is that the police were being seen as the ones in charge and therefore able to dictate what needed to happen next. As we saw above, Child Q herself told the reviewing team that the officers “took me away from the people who were supposed to protect me”. Throughout children’s involvement with educational settings they are inherently taught that every adult is a safe adult and that collectively we will act to protect children in our care. Safeguarding of children is a multi-agency responsibility which includes challenge of other professionals where necessary. Therefore, regardless of whether there is formal identification of someone as an appropriate adult, as a safeguarding response we should be considering necessity and proportionality of the proposed action and asking whether there is a less restrictive option that would achieve a similar outcome (if such as action is required at all). If we do not consider the proposed action to be necessary and proportionate, then ask for an inspector or above to review the decision making.

- Does the child understand what is being proposed? The role of the appropriate adult is to aid understanding. Therefore we need to ensure that the child is spoken to in an age appropriate manner and using words that they understand, with this understanding being checked. We often hear in change management courses that individuals are more likely to accept change if they understand why the change is required and how it will affect them (i.e. work with as opposed to do unto), thus following a key principle of restorative practice in working with the child or young person.

- If consent is required, does the young person understand what they are consenting to? Checking this follows the principles of the functional test in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (s3), that is does the child or young person understand the information relevant to the decision (i.e. what is going to happen, what are the consequences of agreeing and what are the consequences of not agreeing), have the ability to retain that information (either in their mind or through some other means, e.g. paper based notes), use that information to facilitate the process of making a decision and then communicate their decision. This is also the case if parents are being asked to consent. If a child / young person / parent cannot evidence completion of this process then they cannot be considered to have given valid consent. More information can be found here.

- Is procedure being followed? If, as a result of completing steps 1-3 above, it is decided that intervention is necessary, is the correct procedure being followed to ensure that the welfare of the child remains paramount? Appropriate adults can intervene at any point to stop a process in order to confirm the welfare of the person they are supporting or to ensure that due process is being followed. This can also include requesting a senior officer to review where necessary.

The overview report relating to Child Q sets out that the search of a child on school premises is and should remain a rare situation. As shown in this insight, if this were to happen in your setting then it should happen through multi-agency agreement with the full involvement of the child or young person.